Third Annual Report on the screening of foreign direct investments into the EU

On 19th October 2023, the European Commission published the Third Annual Report[1] on the application of the EU Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) Screening Regulation[2]. Differently to the previous year in which the report was published together with the dual use report, this year it is released jointly with the statistical update[3] on the implementation of the EU Export Control Regulation of dual use items (Regulation (EU) 2021/821)[4].

The report covers the period 2022 and provides insight on how FDI screening works in the EU and how national screening mechanisms are evolving. It contains key information on the main trends of FDI in the EU, legislative developments and FDI screening activities in Member States, while the last section discusses the EU cooperation mechanism.

Regarding the main trends, a global decrease was reported with EUR -140 billion of inward FDI in the EU27 compared to +142 bn in 2021, while in the long term, the EU27 recorded an increasing trend in the number of greenfield investments and foreign acquisitions[5] between 2015 and 2022. In terms of origin, the United States (US) accounts for 32.2% of all foreign acquisitions and 46.5% of all greenfield investments, followed by the United Kingdom with 25.1% and 19% of acquisitions and greenfield investments respectively. Despite an overall decrease in foreign investment between 2021 and 2022, the number of greenfield investments from the US and Offshore Financial Centres[6] increased by 13.7% and 8.5% respectively. The number of acquisitions, on the other hand, will show a general decline, except for Japan and India with robust growth of 23.9% and 107.1% respectively. The EU27 destinations of these investments followed the same downward trend. However, Germany remained the main destination of acquisitions with a share of 17%, followed by Spain with a share of 13.5%. For greenfield investments, Spain was in first place with a proportion of 17.2%, followed by France and Germany with 14% and 11.4% respectively. Finally, the five main sectors, namely ICT, manufacturing, PST, finance and retail recorded a decrease in the number of acquisitions, while greenfield investments increased, except for manufacturing. The sector with the highest share of investment in acquisitions was ICT, while retail was the leading sector for greenfield investments.

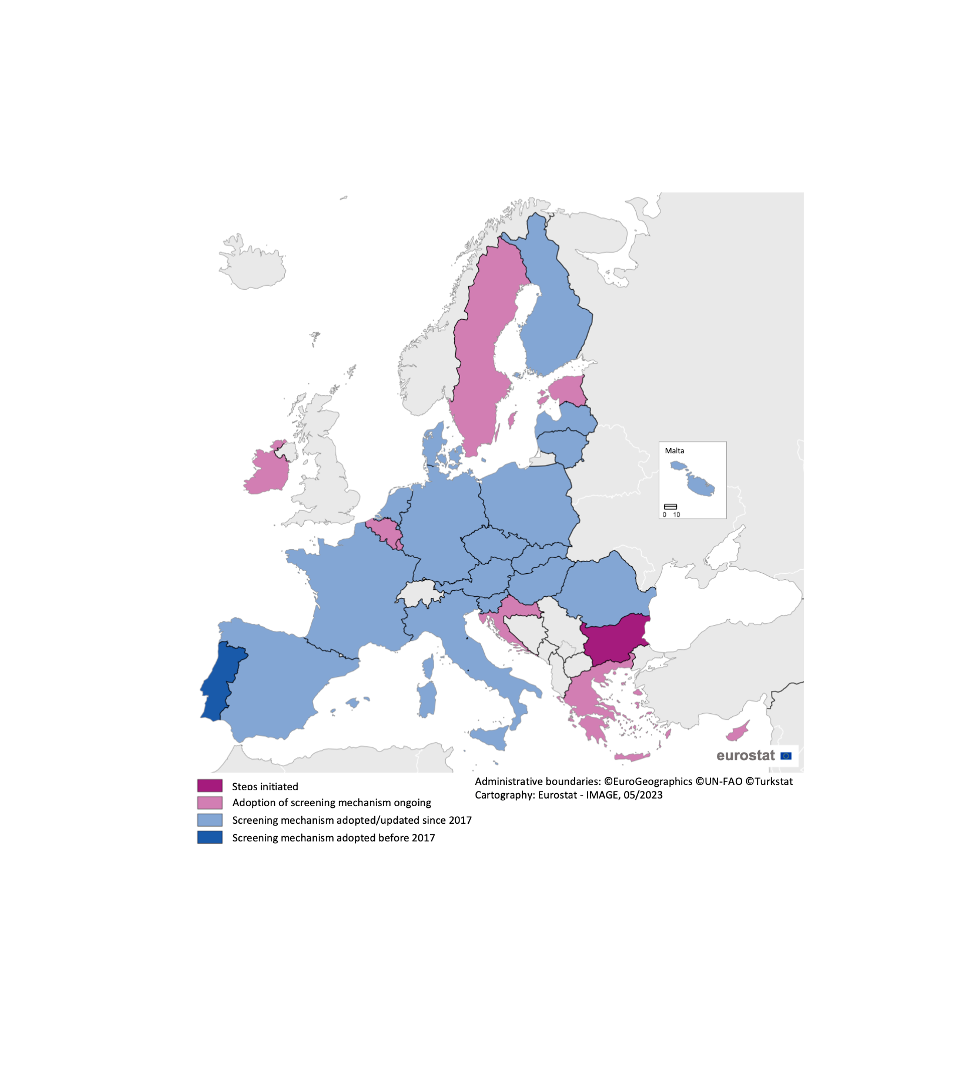

With respect to legislative developments in Member States and in line with the provisions of Article 3(7) of Regulation (EU) 2019/452, many Member States notified the adoption of new national screening mechanisms or the update and extension of existing ones in response to Russia’s war of aggression against Ukraine. Specifically, 7 Member States[7] already have their national FDI screening mechanism in place, 8 countries[8] updated it in 2022, while another 8[9] had a consultative or legislative process that is expected to lead to the adoption of a new mechanism. The Netherlands and Romania have started the process of updating their existing mechanism. Slovakia was the only country to adopt a new mechanism in 2022.

The EU Regulation 2019/452 set up a cooperation mechanism for the screening of FDI between the European Commission and EU Member States, as well as among Member States, based on the exchange of information on transactions subject to screening at national level. The Member States have reported a total of 1444 requests for acquisition approvals from foreign investors, with an unequal distribution of these requests across Member States[10]. In 2022, about 55% of the cases were formally screened, while in 2021 it was only 29%, showing an increase in the percentage of formally screened cases. However, whether a case should be screened depends on the national legislation and the way it classifies and treats applications.[11] Among the cases that were formally screened in 2022, 86% were approved without any conditions. In contrast, this was 73% in 2021. 9% of the decisions included an approval with conditions or mitigating measures which is lower than in 2021 (23%). In 4% of situations, the involved parties withdrew before a decision was taken and, finally, 1% of transactions were blocked.

Under the EU cooperation mechanism, the number of countries submitting notifications increased from 13 to 17 between 2021 and 2022, with a total of 423 notifications; six of these countries[12] accounted for 90% of the notifications transmitted in 2022. Based on these notifications, the manufacturing[13] sector had the highest number of transactions with a share of 27%. In terms of the value of the transactions, 49% had a value of less than EUR 500 million (62% in the previous report). In respect of the procedures and speed of completion of FDI cases, 81% of notified cases were closed by the European Commission in phase 1 and only 11% went to phase 2.[14] Manufacturing was the main sector investigated in phase 2, accounting for 59% in 2022 (compared to 44% the previous year). Regarding the origin of investors subject to FDI screening, the top six countries[15] remained the same as in 2021, with the US topping the list with 32% of notified cases, down from 40% in 2021. Conversely, the proportion of notified cases originating from countries other than the top six increased from 29% in 2021 to 40% in 2022, indicating a greater shift in the origin of FDI. In addition, 20% of the notified cases were multi-jurisdictional FDI transactions.[16] Last but not least, the European Commission issued opinions[17] under Article 7(5) of the Regulation[18] in just 3% of the cases notified by Member States.

In closing, it should be noted that in April 2022, the European Commission adopted a guideline[19] on FDI from Russia and Belarus, which pays special attention to critical EU assets of entities or individuals that are in any way linked to the Russian or Belarusian governments. Finally, the data presented in the report showed that the EU mechanism allowed to prevent investments posing security or public order risks without restricting the overall flow of foreign investment to the EU, while the overall decrease in total FDI to the EU is due to the general economic slowdown and rising financing costs due to higher interest rates and weakening confidence in the global market.

[1] Report from the Commission to the European Parliament and the Council Third Annual report on the screening of foreign direct investments into the Union, 19/10/2023, available at https://ec.europa.eu/transparency/documents-register/detail?ref=COM(2023)590&lang=en.

[2] Regulation (EU) 2019/452 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 19 March 2019 establishing a framework for the screening of foreign direct investments into the Union (OJ L 79I, 21.3.2019, p. 1).

[3] The statistical update on the implementation of the Export Controls Regulation published by the European Commission complements the 2022 Annual Export Control Report Available at https://circabc.europa.eu/ui/group/654251c7-f897-4098-afc3-6eb39477797e/library/d45b2bfc-7029-412a-aa1e-b59ac87433f8/details?download=true.

[4] Regulation (EU) 2021/821 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 20 May 2021 setting up a Union regime for the control of exports, brokering, technical assistance, transit and transfer of dual-use items (recast), (OJ L 206, 11.6.2021). Available at:https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/reg/2021/821/oj.

[5] FDI can take two different forms: greenfield, and mergers and acquisitions (M&As). International greenfield investments typically involve the creation of a new company or establishment of facilities abroad, while an international merger or acquisition amounts to transferring the ownership of existing assets relating to an economic activity to an owner abroad.

[6] The main offshores by number of M&As or Greenfields are (in alphabetical order): Bermuda, British Virgins Islands, Cayman Islands, Mauritius and the United Kingdom Channel Islands. For the full list of Offshore Financial Centres, see e.g., Commission Staff Working Document – Following up on the Commission Communication “Welcoming Foreign Direct Investment while Protecting Essential Interests” – SWD (2019) 108 final – 13 March 2019.

[7] Czechia, Denmark, Germany, Finland, Malta, Portugal and Slovenia.

[8] Austria, France, Hungary, Italy, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland and Spain.

[9] Belgium, Croatia, Cyprus, Estonia, Greece, Ireland, Luxembourg, Sweden.

[10] the top four Member States accounted for 66% of all authorization requests in 2022, down from 70% in 2021 and almost 87% in the first report.

[11] Member States have different screening procedures. So, the cases reported depend on the domestic procedures (scope, eligibility check upfront or later, etc.). For instance, some Member States declared cases ineligible before a formal screening procedure is carried out, while others first formally screened cases and then declared them ineligible. The graphs and numbers reported in this chapter aim at accurately reflecting Member States’ screening activities as reported by them, regardless of their domestic system.

[12] The six Member States are: Austria, Denmark, France, Germany, Italy and Spain.

[13] Manufacturing encompasses activities by companies which are involved in the transformation of materials into new products. For example, this encompasses the manufacturing of electrical equipment and motors, of industrial machinery and equipment, of weapons and ammunitions, of pharmaceuticals, etc.

[14] Phase 2 implies a more detailed assessment of cases that could possibly affect security or public order in more than one member state. When opening phase 2, the European Commission requests additional information which varies, depending on the transaction and detail of the information supporting the notification. The information requested may include one or several elements such as: data on products and/or services of the target company, possible dual-use classification of any products involved, customers, alternative suppliers and market shares, influence of the investor on the target company after the transaction, IP portfolio and R&D activities of the target company, additional defining characteristics of the investor and its strategy.

[15] USA, the UK, China, Japan, the Cayman Islands and Canada.

[16] “Multi-jurisdiction FDI transactions” refers in this context to FDI transactions where the target company is a corporate group with a presence in more than one Member States (and possibly also third countries), e.g., by way of subsidiaries in more than one Member State. Depending on the circumstances, and the particularities of the screening mechanism of the relevant Member States such deals are notified by more than one Member State, albeit rarely in a coordinated and synchronised manner.

[17] Opinions remain confidential pursuant to Article 10 of the Regulation and are issued only when and if required by the circumstances of a case, more specifically the risk profile presented by the investor and the criticality of a target company. When an opinion is issued, any recommended mitigating measures are proportionate and specific to the risks and criticality identified. European Commission’s opinions may also consist of sharing relevant information with a screening Member State and may also suggest potential mitigating measures to address identified risks. It is ultimately for the Member State where the investment takes place to decide on the transaction, while it shall give due consideration to any European Commission opinion. Opinions relating to projects and programs of Union interest are shared with all Member States.

[18] Article 7(5) states that “Where a Member State or the Commission considers that a foreign direct investment which is not undergoing screening is likely to affect security or public order as referred to in paragraph 1 or 2, it may request from the Member State where the foreign direct investment is planned or has been completed the information referred to in Article 9.”

[19] Communication from the Commission – Guidance to the Member States concerning foreign direct investment from Russia and Belarus in view of the military aggression against Ukraine and the restrictive measures laid down in recent Council Regulations on sanctions (OJ C 151 I, 6.4.2022, p. 1).

No responses yet